A nugget from the archives around how forms of writing and research are affected by the tools we use…

Writing Bricks

Rebecca Roach

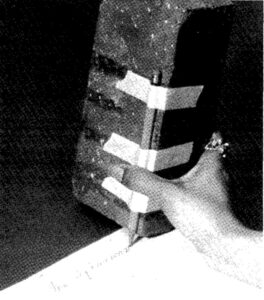

This image is from a report written by Doug Engelbart, engineer and computer scientist best known for developing the computer mouse. Its a “writing brick”. Or at least, a pencil taped to a brick.

The writing brick was part of Engelbart’s efforts, with colleagues at the Augmentation Research Centre (part of the Stanford Research Institute) to fulfil a lofty goal: developing computer tools and a personal workstation that could serve a much grander ambition of ‘improving the intellectual effectiveness of the individual human being’. Engelbart wasn’t alone in his sense of purpose. Vannevar Bush, another key figure in the history of computing, had proposed the “Memex” machine as a means by which to overcome the information overload that threatened scientists and scholars in the 1940s. Bush didn’t use bricks, his thinking was more around mimeography.

The writing brick hasn’t garnered the publicity that the computer mouse has. It wasn’t part of the “mother of all demos”: the 1968 moment where Engelbart demoed the results of his team’s work – the mouse, graphics, video conferencing, hypertext and other systems and hardware now commonplace in personal computing devices. Nor is it the metaphor by which Engelbart’s DIY approach is known (all things being equal it should be “brick-strapping”, not “bootstrapping”). But that is not to say it wasn’t important.

In a later talk for the Association of Computing Machinery conference on the History of Personal Workstations, Engelbart explained why he forced his colleagues to write with bricks.

it’s only a matter of happenstance that the scale of our body and our tools and such lets us write as fast as we can. What if it were slow and tedious to write? A person doesn’t have to work that way very long before starting to realize that our academic work, our books-a great deal would change in our world if that’s how hard it had been to write.

Engelbart’s point was not really about technological determinism, he was making a point about thinking outside the design box. But as he notes, our knowledge work and objects are themselves shaped by the affordances of specific writing technologies.

As our writing technologies change, how might we reimagine our academic work and objects? What might that writing brick experiment suggest to us almost 50 years later?